Of Forests and Grasslands: Human-Animal Interactions and Paleoecology in Late Pleistocene-Holocene Sri Lanka

New study provides detail into human hunting strategies in tropical Sri Lankan forests

Sri Lanka has emerged as a key region for understanding how early human groups adapted to tropical environments, specifically challenging the notion that rainforests were ecological barriers to early human dispersals. Archaeological research on the island has provided direct evidence from as long as 48,000 ago years of humans utilizing rainforest resources, such as specialized hunting of small-bodied, agile prey, such as monkeys and squirrels, gathering of freshwater molluscs and processing of plant materials.

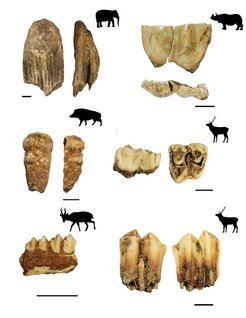

These activities were made possible by microlithic stone tools and bone implements, including the earliest bone-and-arrow documented so far outside Africa, as well as tools for working animal skin and plant fibres. In addition, stable isotope analyses of animal and human teeth from archaeological sites in Sri Lanka have also provided additional, clear evidence for the overall reliance of early human foragers on rainforest resources.

Despite this recent increase in knowledge, the ways human populations and the animals they relied on responded to major climatic changes remain relatively under explored. In a recent paper, a team of international researchers led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology published results of stable isotope analyses of some 300 animal and human teeth from Fa-Hien Lena and Kitulgala Beli-lena in Sri Lanka, providing additional insights into the adaptations of hunter-gatherer groups in tropical environments through time.

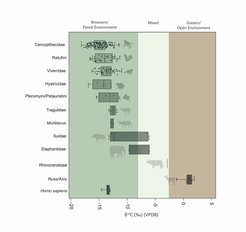

Geochemical analyses of human teeth confirmed a heavy reliance on rainforest resources during the last 12,000 years. Similarly, a majority of the animal specimens the researchers studied, including monkeys, squirrels and civet cats, showed stability in canopied rainforest habitats throughout time. However, data from larger animals, including deer and pigs, suggests that humans also exploited different ecological niches.

Specifically, stable carbon isotopes from deer teeth found in archaeological layers dated to roughly 10,000-12,000 years ago suggest that human populations living in rainforests had access to resources from more open environments, suggesting either hunting expeditions to grasslands or trade with communities living in these environments. Detailed analysis of animal remains shows that deer were not a significant food source for the human groups that inhabited the sites and that deer skeletal elements were brought to the site most likely as materials for tool and ornament production.

The data also suggest some changes in forest cover in/or around the sites, with Fa-Hien Lena showing increase in canopy cover following the onset of the Holocene and Kitulgala Beli-len by contrast being more open.

Finally, the researchers provide evidence for the presence of rhinoceros in the island during the Holocene. A fragmented rhino tooth most likely representing the Indian rhino, Rhinoceros unicornis, from an Early Holocene layer (ca. 10,000 years ago) in Fa-Hien Lena showed evidence that the animal lived in a mixed environment of open forests and woodland. The evidence from this now locally extinct taxon highlights human interactions with large mammals even as they focused on hunting small animals for subsistence.

These findings open future avenues of research into prehistoric forager mobility patterns across different environments in Sri Lanka as well as changes in the niches occupied by animals that humans relied on resulting from environmental change.