Past Human Impacts on the Tropics and Connected Earth Systems

The last 5 years of research in the tropics have not only started to demonstrate the long record of human presence emphasized above, but also the fact that human societies have left legacies of varying nature and intensity on different aspects of tropical ecosystems and their associated earth systems. This project applies varied methods to build detailed records of human interactions with different aspects of these environments across space and time including:

Soils – changing the earth

Soil erosion is one of the greatest challenges facing the tropics in the coming decades (State of the Tropics, 2020). While archaeologists are often on the lookout for monumental buildings as key indicators of human presence and impacts, in tropical contexts human management of soils has emerged as one of the most obvious and lasting traces of human presence. In the Amazon Basin, for example, Amazonian Dark Earths have been observed along the Amazon River and its tributaries, sometimes stretching for kilometres.

This part of the project will analyze sediments from archaeological and palaeoenvironmental sequences to explore how humans modified tropical soils in the past. Working with sedimentologists and geologists at Friedrich Schiller Universität, Deutsches Geoforschungszentrum Potsdam, and the Max Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, the group will use geochemistry (including stable isotope analysis) and micromorphology to determine the degree to which these anthropogenic soils are a pan-tropical phenomenon, as well as the unique characteristics that could make them useful for food producers in different regions today.

Fire dynamics - A burning question

The last few years have seen dramatic wildfires sweep across the tropics, with smoke often being carried thousands of kilometres between continents. From our current perspective, the use of fire in tropical forests seems inevitably destructive and ultimately ill-advised. However, there is increasing evidence for Indigenous fire use in the tropics to manage vegetation structure, to clear understories, and to promote certain resources. Indeed, cessation of these fire dynamics during the colonial period, or under the guise of modern conservation, has often led to unintended consequences.

Working with partners in the Department of Archaeology, this part of the project will undertake charcoal and microcharcoal analyses, as well as biomarker analyses, on archaeological and palaeoenvironmental sediments, as well as from the rings of living trees, to explore how fire regimes have changed in different parts of the tropics over time. By exploring changing fire intensity and frequency, the group will be able to document how different societies have altered fire and ecosystem dynamics, from the deep past up to recent history and the present.

Species and nutrient flows – from megafauna to island biodiversity

The abundance of plant and animal life found in tropical forests makes them critical sites for exploring how past human societies have impacted biodiversity. Here palaeontology, zooarchaeology and archaeobotany can be used to discern changes in species distributions and behaviour following the arrival of humans. Meanwhile, stable isotope analysis can be used to explore how faunal diets and mobility after the appearance of humans in different tropical contexts.

This part of the project will work with partners in the Department of Archaeology to apply zooarchaeology and archaeobotany to archaeological sites in different parts of the tropics to investigate how biodiversity has been impacted by different human societies and economies in the past. Focusing on megafauna, the group will work with the ‘LASTJOURNEY’ ERC team, among others, to apply isotope analysis to Pleistocene megafaunal remains to see how migrating behaviour and ecologies varied following the arrival of the first humans in South America.

Trees and landscapes

There is growing evidence that humans have had a major impact on the distribution and structure of tropical forests themselves. The isoTROPIC group is pioneering the use of dendrochronology and historical ecology of living tropical trees to explore past human management practices in the Amazon Basin. Similarly, we also apply palaeoenvironmental coring and the application of pollen, phytolith, and plant biomarker isotope analysis to sediments in order to explore changes in local and regional forests – including the scale of human clearance.

This part of the project seeks to expand the use of tropical dendrochronology and tropical palaeoenvironmental archive analysis in archaeological contexts. The group will apply dendrochronology to long-lived trees in the Americas, Africa, and Asia to determine the degree to which forest management changed following the arrival of colonialism. Meanwhile, palaeoenvironmental coring of lakes and natural records will be used to explore questions such as the impact of the spread of rice agriculture in Asia and the degree to which forest cover changed following the arrival of Europeans and cessation of Indigenous management in parts of the tropics.

Earth systems - a tropical ‘Anthropocene’

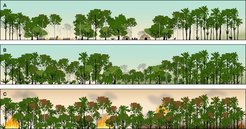

Given that tropical forests are evidently locked into a series of earth systems, observations of past human-induced changes to these habitats raise the possibility that human societies may also have initiated early regional, and even global, changes to earth systems. As Figure 1 shows, by combining data from the above areas it is possible to develop land-use maps, and thus landcover change maps, for different parts of the tropics at different points in time, as well as their potential for earth systems change.

This part of the project will build on the current activities of the PANTROPOCENE project to develop pan-tropical land-use maps for different parts of the tropics. In so doing it will explore the degree to which Pleistocene hunter-gatherers, Holocene food producers, tropical urban dwellers, and European colonial impacts might have initiated earth systems changes to different degrees. In so doing, we can start to observe the degree to which past human actions have left legacies and challenges for contemporary societies, and quantitatively assess the scale of human influence occurring today in comparison to the past.