Stone Fruit from the Stone Age: The Earliest Known Olive Use in Africa

A recent study published in the journal Nature Plants examines charcoal and pit fragments to reveal that people were already using olives as food and fuel 100,000 years ago

In the Mediterranean region, humans have relied on olives as a source of food, fuel, and ingredients for medicine and cosmetics since the Neolithic period. Because of its valuable oil, the olive tree was one of the first trees to be cultivated for agriculture 6000 years ago, but its presence in mythology reaches even further back in time. Prior to the Neolithic, however, olive finds are more rare, due in part to the wild olive’s limited distribution during the last Ice Age. But recent research has shown that the wild olive could have survived in various refugia during the last glacial period, the largest being Morocco’s Atlantic coast and the southern Iberian Peninsula.

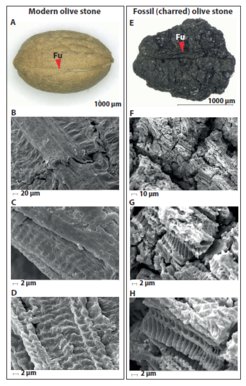

In a new study, scientists led by Dr. Laurent Marquer from the Institute of Botany at the University of Innsbruck reveal evidence that olives were already used by humans 100,000 years ago. The researchers analyzed charcoal and charred fragments of plant pits found in the sediment of two caves in northern Morocco. Of the pits found, 81% were wild olives.

Olives for food and fuel

The El Mnasra and El Harhoura caves have yielded valuable Stone Age finds since their discovery in 1956 and 1977, including worked shells and tools made of stone and bone. Dr. Eslem Ben Arous, researcher from the ‘Lise Meitner’ Pan-African Evolution research group at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and from the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana, led the geochronology study that made it possible to date and contextualize the finds.

For El Mnasra cave, which delivered the most significant results for the Middle Stone Age, several dating methods were used: the OSL, US-ESR and a Bayesian model published by Eslem Ben Arous et al. in the journal PLOS ONE have re-examined the entire chronology.

“The supplementary radiocarbon dating allow us to confirm that the remains studied were indeed in situ although we sampled them from the excavation directly,” says Ben Arous. “The recent discovery of olive pits sheds new light on the behaviors of hunter-gatherers in a crucial region for the evolution of our species.”

Although the study could not definitively prove whether the inhabitants of El Mnasra and El Harhoura ate the olives or only used them as fuel, the condition of the pits suggests that the fruits were deliberately broken before being burned.

"It would be possible that whole olive branches were thrown into the fire and the fruit hanging from them simply burned," explains Marquer. "However, the fact that the olive pits were found broken into many small pieces speaks against this. There's every indication that people first ate the fruit and then deliberately broke the pits to burn them more efficiently."

Olive pits contain a lot of oil and lignin, a molecule responsible for the formation of wood. The residue from broken olive pits creates a slow-burning fire that is great for cooking. Dried pit fragments also produce smokeless flames, which would have been a great advantage, especially for cave dwellers.

The early use of wild olives in Africa by Middle Stone Age groups from roughly 100,000 years ago might represent improvements in cooking, wood processing and social organization, among other aspects. This finding provides new insights into the understanding of Middle Stone Age hunter-gatherer economies, a foreshadowing of the story of the iconic olive tree in the Mediterranean.