Agropastoralists in Central Tibet Chose a Barley-Based Farming System by 3,000 Years Ago

New research pushes this development back roughly 1,000 years and sheds light on motivating factors

When we think of barley, the first thing that comes to mind is probably beer or whiskey. However, in Tibet, barley is a dietary staple, forming the basis of most people’s daily meal: tsampa, a roasted barley flour that plays a critical role in the local culture. Barley-based agriculture may also have been one of the key factors in the adaptation of farming to the challenges of life at high elevations and in the demographic success of the ancient Tibetan Empire. However, we know little about when this specialized barley-based farming economy emerged in Tibet or why ancient agropastoralists chose to take the risk of focusing almost exclusively on one crop.

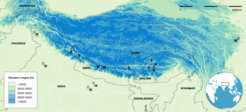

In a new study published in Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, a team of researchers from Sichuan University, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, the Tibetan Cultural Relics Conservation Institute, and Washington University in St. Louis provide new systematic evidence of barley-based agricultural development at least 1,000 years earlier than previously believed. Their excavations of the Bangga settlement site (1055-211BC) in central Tibet clarifies the questions of when and why the transition to a single-crop agricultural system occurred.

“Our knowledge of early agriculture on the Tibetan Plateau is mainly based on the evidence from the northeastern margin. We know little about what occurred on the central plateau, due to the lack of systematic excavation and sampling,” says corresponding author Prof. Hongliang Lu from Sichuan University.

Previous research at the sites of Qugong and Changguogou in central Tibet, although limited, suggests that a mixed crop system, including two species of millet, barley, wheat, and buckwheat was practiced from 3,500 to 3,000 years ago. At the Kaerdong site in western Tibet, researchers have found evidence of a barley-dominant system by around 1,800 years ago.

“These findings leave us with a 1,000-year time gap,” says lead author Li Tang, “and because these materials were all collected from small-scale test trenches, it was difficult for us to pinpoint when and why the transition to a barley-dominant economy occurred.”

In their new paper, the international team reports the first large-scale archaeobotanical assemblages in central Tibet. During a four-year period of systematic excavation of the Bangaa site, Professor Lu and his team analyzed 80 flotation samples (1144.9 liters) from different cultural layers and stone enclosures.

Their results show that a stable barley-based economy was practiced at Bangga as early as roughly 3,000 years ago.

“Crop transitions are usually tied to complex sets of factors,” says Dr. Robert Spengler of the Max Planck Institute. “We speculate that a combination of factors drove this specific crop transition, including cold tolerance, low irrigation requirements, fuel-saving qualities, and benefit for a mobile pastoralism lifestyle.”

From an ecological perspective, barley’s high tolerance of frost and dehydration, relative to wheat and millets, probably made it an ideal crop to protect food security in high-altitude regions of Tibet.

There were likely social reasons for this transition as well. Tibet’s low-oxygen, low-pressure environment make boiling or steaming, as is common with millet and wheat-based foods, more fuel and time demanding. Barley, however, can be roasted and ground into flour with comparatively small investments of time and fuel. These advantages would have been valuable to agropastoralists, and may have stimulated the development of a new barley-flouring culinary practice for its portability, durability, and fuel-efficiency.