Seasonal Seafood in the Mesolithic: New study reveals humans foraged molluscs in winter for better meat returns

The Mesolithic of Cantabria, northern Spain, like other regions in Atlantic Europe, is characterised by a marked increase in the human use of coastal resources and the formation of the so-called shell middens. Archaeological investigations have provided insights into the formation processes of these shell middens, as well as long-term changes in human exploitation of different marine resources and the relationship of foraging strategies to climate changes. However, efforts to reconstruct the key environmental factors governing coastal subsistence and foraging resilience, the seasonal availability and use of different marine resources, has been limited in the region, and indeed across coastal Mesolithic Europe more widely.

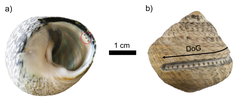

Sampling procedures applied for the extraction of calcium carbonate micro-samples from the aragonite layer.

In a new study published in the Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences Journal, two members of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (Asier Garcia-Escarzaga and Patrick J. Roberts), in collaboration with scholars of two Spanish universities, have applied oxygen isotope analyses on mollusc shells to determine the season in which this food supply was harvested by humans. The authors proved that not only did the stable oxygen isotope measurements of Phorcus lineatus (da Costa, 1778), a common mollusc found at Mesolithic sites in Cantabria, track the season of growth, but that this methodology could be used at the site of El Mazo cave to provide high-resolution insights into human consumption choices and the seasonality of mollusc collection through time.

Seasonality of Phorcus lineatus collection by stratigraphic unit (SU). The figure shows the absolute number (bars) and the percentage (pies) of samples assigned to each season.

The results of the study highlighted that molluscs were consistently harvested during the coldest months (late autumn and winter) throughout the entire shell midden sequence, in agreement with data previously obtained for this species elsewhere along the Atlantic façade of Europe. Following an experimental programme in which modern samples were collected throughout three complete years, the authors were able to demonstrate that winter collection coincided with the period of maximum meat yield of this taxa in northern Spain. This investigation demonstrates for the first time that mollusc collection patterns in Mesolithic Spain were driven by a cost-benefit principle and that human populations had intimate knowledge of the seasonal developmental cycles of exploited marine taxa.