New techniques in the field of ancient pathogens genomics aid research on infectious diseases

A team of scientists at the forefront of ancient infectious disease research has published an important review of the field in Nature Reviews Genetics. Over the past decade, discoveries about infectious diseases have been made thanks to cutting-edge technologies for use on ancient DNA. By directly examining the DNA of pathogens like bacteria, viruses and parasites from archaeological remains, researchers have been able to trace how they spread and evolved, giving important insights not only into important aspects of human history, but also increasing our understanding of modern infectious disease.

The study of ancient pathogen genomics is a relatively young field. Traditionally, past infectious diseases have been studied by examining the physical structure of ancient skeletons that showed signs of disease. However, most infectious diseases do not leave visible traces on bones. Historical records and genetic analysis of modern diseases are other important techniques. However, only since the 1990s has it become possible to study ancient diseases using genetics. Since that time, technological advances in the field of ancient genomics has greatly expanded the ability to study not just people but also diseases in the past.

A team at the forefront of the field of ancient pathogen genomics, including Maria Spyrou, Kirsten Bos, Alexander Herbig and Johannes Krause of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, has published a thorough review of the state of the field in Nature Reviews Genetics, laying out the recent methodological advancements, persistent challenges, and the novel revelations that have been made.

New techniques to answer long-standing questions about ancient diseases

Traditional methods, such as modern pathogen genomics, palaeopathological evaluation of ancient skeletons, and historical records, are all still important tools used by the researchers. However, when combined with analyses of ancient pathogen DNA, the results can be game-changing.

“In the past decade, the reconstruction of ancient pathogen genomes has complemented such traditional analyses with direct molecular evidence, often revealing aspects of past infections that were unexpected on the basis of existing data,” explains Bos. “For example, Hepatitis B was recently discovered in a mummified individual, who showed a rash typically associated with a different disease. Without the use of ancient genomics, the diagnosis would likely have been different,” adds Spyrou.

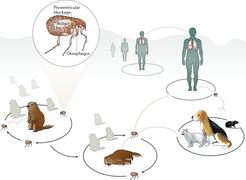

The team concludes that ancient pathogen genomics has shown a great deal of promise in answering previously unanswerable questions about diseases in the past, and that its potential is just beginning to be utilized. “In recent studies on the plague-causing bacterium Yersinia pestis, for example, ancient DNA exploration of its evolutionary past has revealed how a predominantly environmental bacterium and opportunistic gastroenteric pathogen developed into an extremely virulent form by acquiring only a few virulence factors,” explains Herbig.

“We eagerly await revelations on a similar scale for other important pathogens that are expected to arise from the use of these new and developing methods,” states Krause. “By combining these results with data from other disciplines such as archaeology, history and palaeopathology, as well as human population genetics, we hope the field can help to build a more complete picture of the relationship between humans and pathogens over time.”