History of Early Settlement and Survival in the Andean Highlands Revealed by Ancient Genomes

Analysis of seven ancient whole genomes reveals adaptations to the high-altitude environment and agrarian lifestyle of the Andes.

Adapted from a press release by the University of Chicago School of Medicine.

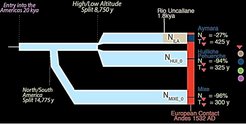

A group led by researchers from the University of Chicago, the University of California Merced, the University of Oklahoma, the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, and the University of Chile used newly generated ancient genomes from seven individuals to study how ancient Andean people—including groups that clustered around Lake Titicaca in Peru and Bolivia, 12,000 feet above sea level—adapted to their environment over the centuries.

In the journal Science Advances, they compared their seven ancient genomes to 64 modern-day genomes from a current highland Andean population, the agropastoral Aymara of Bolivia, and the lowland hunter-gatherer Huilliche-Pehuenche in coastal Chile.

Ancient whole genomes dating to over 7,000 years ago

The goals were (1) to date the initial migration to the Andean highlands, (2) to identify the genetic adaptations to the high-altitude environment that allowed that settlement, (3) to estimate the impact of the European contact starting in the 1530s that caused the near annihilation of many lowland communities of South America.

“Using advanced techniques, we were able to reconstruct the genomes of ancient Peruvians who lived over the past 7,000 years,” explained Christina Warinner of the University of Oklahoma and the Max Planck Institute of the Science of Human History, who led the laboratory analysis.

“Those early settlers have the closest affinity to the people who now live in that area. This is a harsh, cold, resource-poor environment, with low oxygen levels, but people there adapted to that habitat and the agrarian lifestyle,” said senior author Anna Di Rienzo of the University of Chicago, who led the population genetic analysis.

Study uncovers adaptations to high-altitude, agrarian lifestyle

The researchers found that highland Andeans experienced much smaller than expected population declines following contact with European explorers who first came to South America in the 1530s. In the lowlands, demographic modeling and historical records infer that up to 90 percent of residents may have been wiped-out after the arrival of Europeans. But the people living in the upper Andes had only a 27-percent population reduction.

Even though the highlanders lived in altitudes above 8,000 feet, which meant reduced oxygen, frequent frigid temperatures and intense ultra-violet radiation, they did not develop the responses to hypoxia seen in natives of other high-altitude settings, such as Tibet.

The Andeans may have adapted to high altitude hypoxia in a different way, via cardiovascular modifications. The researchers found evidence of alterations in a gene called DST, which is associated with the formation of cardiac muscle. Andean highlanders tend to have enlarged right ventricles. This may have improved oxygen intake, enhancing blood flow to the lungs.

But the strongest adaptation signal the researchers found was in a gene called MGAM (maltase-glucoamylase) an intestinal enzyme. It plays an important role in the digestion of starchy foods such as potatoes—a food native to the Andes. A recent study suggests that the potato may have been domesticated in the region at least 5,000 years ago. Positive selection on the MGAM gene may represent an adaptive response to greater reliance upon starchy domesticates.

The early presence of this variant in Andean peoples suggests “a significant shift in diet from one that was likely more meat based to one more plant based,” said Mark Aldenderfer of the University of California, Merced, an anthropologist specializing in high-altitude populations. “The timing of the appearance of the variant is quite consistent with what we know of the paleo-ethno-botanical record in the highlands.”

Although Andean settlers consumed a high-starch diet after they started to farm, their genomes did not develop additional copies of the starch related amylase gene, commonly seen in European farming populations.

Immune-related genes increased in prevalence after contact with Europeans

A comparison of the ancient genomes with their living descendants also revealed selection for immune-related genes soon after the arrival of Europeans, suggesting that Andeans who survived may have had an advantage with regard to the newly introduced European pathogens.

“Contact with Europeans had a devastating impact on South American populations, such as the introduction of disease, war, and social disruption,” explained John Lindo of the University of Chicago. “By focusing on the period before that, we were able to distinguish environmental adaptations from adaptations that stemmed from historical events.”

“In our paper,” said Aldenderfer, “there was none of this prioritization of genes at the expense of archaeological data. We worked back and forth, genetics and archeology, to create a narrative consistent with all of the data at hand.”