Aboriginal Hair Shows 50,000 Years Connection to Country

DNA in hair samples collected from Aboriginal people across Australia in the early to mid-1900s has revealed that populations have been continuously present in the same regions for up to 50,000 years – soon after the peopling of Australia.

Published today in the journal Nature, the findings reinforce Aboriginal communities’ strong connection to country and represent the first detailed genetic map of Aboriginal Australia prior to the arrival of Europeans.

These are the first results from the Aboriginal Heritage Project, led by the University of Adelaide’s Australian Centre for Ancient DNA (ACAD) in partnership with the South Australian Museum.

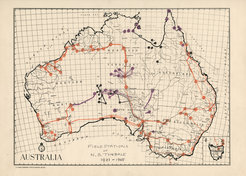

Researchers analysed mitochondrial DNA from 111 hair samples that were collected during a series of remarkable anthropological expeditions across Australia from 1928 to the 1970s and are part of the South Australian Museum’s unparalleled collection of hair samples.

Mitochondrial DNA allows tracing of maternal ancestry, and the results show that modern Aboriginal Australians are the descendants of a single founding population that arrived in Australia 50,000 years ago, while Australia was still connected to New Guinea. Populations then spread rapidly – within 1500-2000 years – around the east and west coasts of Australia, meeting somewhere in South Australia.

“Amazingly, it seems that from around this time the basic population patterns have persisted for the next 50,000 years -showing that communities have remained in discrete geographical regions,” says project leader Professor Alan Cooper, Director of ACAD, University of Adelaide.

“This is unlike people anywhere else in the world and provides compelling support for the remarkable Aboriginal cultural connection to country. We’re hoping this project leads to a rewriting of Australia’s history texts to include detailed Aboriginal history and what it means to have been on their land for 50,000 years – that’s around 10 times as long as all of the European history we’re commonly taught.”

A central pillar of the Aboriginal Heritage Project is that Aboriginal families and communities have been closely involved with the project from its inception and that analyses are only conducted with their consent. Importantly, results are first discussed with the families to get Aboriginal perspectives before scientific publication. The research model was developed under the guidance of Aboriginal elders, the Genographic Project, and professional ethicists.

This is the first phase of a decade-long project that will allow people with Aboriginal heritage to trace their regional ancestry and reconstruct family genealogical history, and will also assist with the repatriation of Aboriginal artefacts.

“Aboriginal people have always known that we have been on our land since the start of our time,” says Kaurna Elder Mr Lewis O’Brien, who is one of the original hair donors and has been on the advisory group for the study. “But it is important to have science show that to the rest of the world. This is an exciting project and we hope it will help assist those of our people from the Stolen Generation and others to reunite with their families.”

“Reconstructing the genetic history of Aboriginal Australia is very complicated due to past government policies of enforced population relocation and child removal that have erased much of the physical connection between groups and geography in Australia today,” says Dr Wolfgang Haak, formerly at ACAD and now at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany.

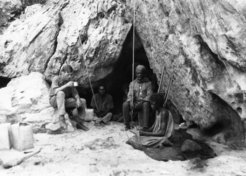

The South Australian Museum’s collection of hair samples, complete with rich cultural, linguistic, genealogical and geographical data, comes from the expeditions run by the Board of Anthropological Research from the University of Adelaide.

“This Aboriginal Heritage Project is able to exist because of the extensive records collected by Norman Tindale and Joseph Birdsell and others on those expeditions, which are held in trust for all at the South Australian Museum. They include detailed information about the birthplaces, family history and family trees, film, audio and written records – allowing a wide range of approaches to be used by this project to reconstruct history,” says Brian Oldman, Director of the South Australian Museum.

“The South Australian Museum’s Aboriginal Family History Unit has also been instrumental to the project and has worked closely with the University team to consult with Aboriginal families and communities to obtain permission for tests to be performed,” he says.

Professor Cooper says: “We are very grateful for the enthusiasm and overwhelming support for this project we have received from Aboriginal families, and the Cherbourg, Koonibba, and Point Pearce communities in particular.”

The research will be extended to investigate paternal lineages and information from the nuclear genome. Team member Dr Ray Tobler, postdoctoral researcher in ACAD with Aboriginal heritage on his father’s side, has an Australian Research Council (ARC) Indigenous Discovery Fellowship to extend the AHP research, to examine how the longevity of Aboriginal populations in different habitats across Australia has shaped the remarkable physical diversity found across modern Aboriginal Australians.

Other research partners include La Trobe University, Deakin University, and the National Centre for Indigenous Genomics. The project is funded by the ARC Linkage Projects scheme with financial or additional research support from the Australian Genome Research Facility, Bioplatforms Australia, the ARC Centre of Excellence for Mathematical and Statistical Frontiers, and the National Geographic Society.