Disentangling the Relationships Between Cultural Traits and Other Variables

Researchers provide guidelines for differentiating between causation and mere correlation in cross-cultural studies.

Recently, a growing number of researchers are hoping to gain insights into human cultural evolution and the diversity of human culture using comparative studies. In essence, this type of work looks for cultural traits or environmental factors that cause other cultural traits – such as the impact that subsistence strategy has on religious beliefs or the impact that the density of rivers has on language diversity. This work has been made vastly more approachable due to the expansion of large databases cataloging the relevant data, and the improvement of the programming and computing power necessary to make these comparisons. However, problems remain because many of the resulting studies make interpretations without controlling for factors that might make cultural variables seem causally related when they are not.

A team of researchers led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and Australian National University has analyzed how to avoid misinterpreting correlations in cross-cultural studies and has identified three sources of non-independence in cultural variables – meaning, the variables are correlated, but are not caused by each other. The three sources identified are: (1) phylogenetic non-independence, meaning that the cultures are related to each other and a shared trait has been inherited by both from a common ancestor culture, rather than developed because it serves the same functional purpose in both cultures; (2) spatial autocorrelation, meaning the cultures share traits because they are geographically close to one another and thereby share many aspects of the same environment and history; and (3) covariation, meaning two traits correlate not because one causes the other but because both are caused or influenced by another variable.

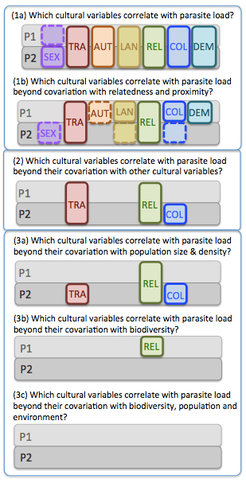

The researchers then lay out guidelines to correct for these sources of non-independence and provide a case-study, looking at the connections between parasite load and various cultural and environmental factors. Parasite load has been hypothesized to have direct and dramatic impacts on a number of cultural traits – including religiosity, sexual behavior, in-group preference and population density. However, by controlling for the three sources of non-independence described above, the authors show that, contrary to previous studies, parasites have no more explanatory power for cultural traits than many other environmental factors like biodiversity, climate and latitude.

The authors emphasize that there are two issues at play with these sources of non-independence. One is whether two variables are correlated in the first place. Correcting for phylogenetic non-independence and spatial autocorrelation addresses this issue. The second is whether the correlation between two variables is evidence of a causal relationship. Correcting for covariation addresses this issue. This is important, because simply finding a correlation between two variables and then hypothesizing a possible causal mechanism between them is not enough to prove causality. “For example, people have hypothesized that the correlation between a high parasite load and lower average IQ is caused by the metabolic costs of infection reducing investment in cognitive development,” explains Simon Greenhill of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “However, this hypothesis is highly problematic as IQ also correlates just as strongly with other measures of biodiversity, such as number of mammal species. But we are not tempted to come up with a hypothesis to explain why having lots of mammal species reduces a nation’s average IQ.”

“Our results suggest that we must be cautious in interpreting these cross-cultural correlations as a reflection of causal connections,” states Greenhill. “Correcting for statistical biases is necessary to avoid being led astray by interpreting incidental associations as meaningful of causal connections.”