Rice Terracing Facilitated Village Growth in Pericolonial Highland Ifugao, Philippines

A new multidisciplinary paper led by scientists at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History combines historical, archaeological, and palaeoecological data into land use models to study the impact of rice agriculture on land-use and demography in the famous Ifugao region of Philippines.

The Ifugao Rice Terraces of the Philippine Islands rank among the world’s most famous agricultural structures and have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1995. For generations, widespread terracing in the mountains of the Philippine Cordillera has allowed the people of the Ifugao region to grow lowland rice as high as 1600 meters above sea level, well beyond the usual limits for wet rice.

Despite their long-standing renown, the terraces’ origins are undetermined. As lead author Max Findley states, “exactly how long the terraces have existed, as well as their impacts on the surrounding tropical forests and landscape, has been a matter of intense debate.”

The Pericolonial Hypothesis

Based on their size and scope, colonial-era researchers and observers assumed the terraces were built over thousands of years. However, research in anthropology, ethnography, linguistics, folk-history, and archaeology over the last eighty years all suggest the terraces were actually built relatively recently, over the course of the last 400 years.

In the last decade, Prof. Stephen Acabado, co-author of the new study and Chair of Anthropology at the University of California Los Angeles, has assembled various lines of evidence to suggest a new theory. He argues that “the terraces were actually built in response to Spanish colonial encroachments, [and they are] the product of a society influenced by, but not subjugated to, a colonial power.” Acabado calls this society pericolonial.

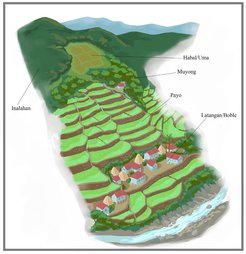

Acabado hypothesizes that some Ifugao peoples moved to the highlands after Spain’s conquest of Northern Luzon’s lowlands (1572-1574) and brought their knowledge of rice cultivation with them. Within generations, the highlands’ pre-existing terrace system for growing taro was repurposed and expanded to cultivate rice. Increased terracing to meet the desire for rice, a ritualistically important crop, in turn catalysed the emergence of a prestige-oriented society split between a rice-consuming elite (kadangyan) and a root-crop-consuming majority who laboured on kadangyans’ terraces (nawotwot). This system of land use relied on terraces (payo), swidden fields (uma), and managed forests (muyong), and it proved highly sustainable.

Models of Land Use

The new paper, released in Frontiers in Earth Science, models and visualizes the expected land use changes of Acabado’s pericolonialism hypothesis. The paper brings together nine scholars from four different continents, six different institutions, and seven academic disciplines. Together, the authors draw upon data from historic documents, archaeological and anthropological fieldwork, and palaeoecological research to generate land use models for Old Kiyyangan Village—the origin-point of terrace rice cultivation in Ifugao folk history—at two timepoints: ca. 1570 and 1800 CE. The earlier point immediately predates the arrival of the Spanish in the lowlands, while the latter was the first year an outside observer recorded seeing the rice terraces.

Comparing the models for 1570 and 1800 showed that the population of Old Kiyyangan Village could have doubled between the two timepoints without causing a corresponding increase in intensive land use. The models in fact indicate that, excluding hunting and gathering, land use would have only marginally increased even as the population grew by 100%. Even more impressive, this would have occurred in spite of the introduction of domestic carabao (water buffalo), a grazing animal, to the village.

The authors argue that this increased land use efficiency stemmed from two key changes in Ifugao agriculture that transpired between 1570 and 1800. First was the marked intensification of land use. Unlike swidden fields, terraces do not need to lay fallow after a set period and therefore consolidated the village’s land use, particularly among the kadangyan. The second change was diversification of crops. Taro was not the only staple crop supplanted between 1570 and 1800. Sweet potato (locally known as camote, based on the Nahuatl word) replaced various yam species as the main staple grown in swidden fields. Since both rice and sweet potatoes are more productive than taro and yams, these crops also helped Ifugao farmers feed a larger population with less land.

Overall, according to senior author Patrick Roberts, “the models demonstrate not only the viability of the pericolonialism hypothesis, but also the advantages that the Ifugao would have derived from increased terracing.”

Implied in this conclusion is that the emergence of what the authors call the “muyong-uma-payo agricultural complex” was essential to Ifugao’s continued rejection of Spanish colonialism. That agricultural system was clearly influenced by the spread of colonialism in the lowlands and the introduction of American crops, but it also melded those influences into the basis for a distinct and independent society.