The Astonishing Origins of a Rebel Language in the Philippines

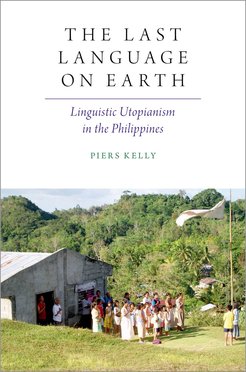

The Last Language on Earth examines the origins and history of the Eskayan language, spoken today by an upland community on the island of Bohol in the southern Philippines. Using linguistic, ethnographic and historical lines of investigation, the new book engages directly with the Eskayan language itself, as well as the direct perspectives of those who use it today.

In 1980, journalists announced the ‘discovery’ of a ‘lost tribe’ on the island of Bohol, Philippines. Speculation about the origins of the group, known as the Eskaya, began almost immediately, with visitors grasping to account for the people’s unique language, dress and beliefs. Some proposed that the Eskaya were descended from Etruscans, or a lost tribe of Israel. Others even accused the group of a hoax, suggesting that they had fabricated their language to attract government support.

But recent research published by Oxford University Press is shedding new light on the enigma.

“I tried to probe the Eskayan language to see what it might reveal about its own history,” says Dr. Piers Kelly, a linguistic anthropologist at the University of New England, Australia, and affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Germany. “But I also wanted to listen to historical perspectives offered by Eskayan speakers today.”

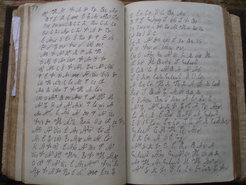

Spoken Eskayan bears little resemblance to Visayan, the native language of the island’s other inhabitants. What’s more, it is written in a complex script of more than one thousand signs. Over several years, Kelly lived and worked alongside Eskaya people, recording their language, literature and writing system.

“The Eskayan language is a riddle,” Kelly concedes. “Its grammar is similar to major Philippine languages, yet most of its vocabulary is a mystery. At a foundational level there is a surprising influence from Spanish and English that can’t be explained through normal borrowing. The symbols belonging to its complex writing system can represent whole words, single syllables, individual letters or a combination.”

Kelly’s linguistic analysis corroborates elements of a traditional story that says that the Eskayan language was intentionally created from scratch. In this popular account, the language and script were both fashioned from the body of an ancestral prophet, and later restored to use in the 20th century by an anti-colonial rebel.

“The island of Bohol is notorious for its long rebellions that have energized political independence movements and local creative practices,” says Kelly. “When US forces invaded the island in 1901 and imposed an English school system by force, there was a motivation to promote a kind of hyper-local Esperanto.”

Still used today by about 550 people, there is a prophecy that Eskayan will one day be spoken by everyone in the world. But for now, Eskaya people remain focused on teaching the language locally. In December 2021, Typhoon Odette destroyed an Eskayan language school and teachers are now looking for resources to restore it. Tribal chieftain Nida Salingay, who worked closely with Kelly to analyze Eskaya literature, said: “We pray that this book will bring a better understanding of our language and history and help to keep our tradition alive.”

The Last Language on Earth will be available via Oxford University Press on April 7.