A Tale of Two Cesspits: DNA Reveals Intestinal Health in Medieval Europe and the Middle East

New research proves the feasibility of retrieving bacterial DNA from ancient latrines

Analysis of 14th-15th century latrines in Jerusalem and Riga, Latvia identifies some of the microbes resident in the guts of these pre-industrial populations, illuminating how gut contents have changed since medieval times.

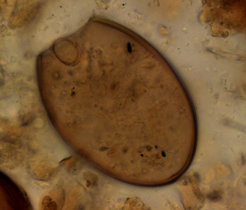

Medieval latrine, c. 1350

A new study published this week demonstrates a first attempt at using the methods of ancient bacterial detection, pioneered in studies of past epidemics, to characterize the microbial diversity of ancient gut contents from two medieval latrines. The findings provide insights into the microbiomes of pre-industrial agricultural populations, which may provide much-needed context for interpreting the health of modern microbiomes.

Over the years, scientists have noted that those living in industrialized societies have a notably different microbiome compared to hunter-gatherer communities around the world. From this, a growing body of evidence has linked changes in our microbiome to many of the diseases of the modern industrialized world, such as inflammatory bowel disease, allergies, and obesity. The current study helps to characterize the change in gut microbiomes and highlights the value of ancient latrines as sources of bio-molecular information.

Ancient Gut Microbiomes: Exploring the Bowels of History

Piers Mitchell of Cambridge University specializes in the gut contents of past people through analysis of unusual substrates. By looking at the contents of archaeological latrines and desiccated faeces under the microscope, he and his team have learned volumes about the intestinal parasites that plagued our ancestors.

“Microscopic analysis can show the eggs of parasitic worms that lived in the intestines, but many microbes in the gut are simply too small to see,” comments Mitchell. “If we are to determine what constitutes a healthy microbiome for modern people, we should start looking at the microbiomes of our ancestors who lived before antibiotic use, fast food, and the other trappings of industrialization.”

Kirsten Bos, a specialist in ancient bacterial DNA from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History and co-leader the study, was first skeptical about the feasibility of investigating the contents of latrines that had long been out of order.

“At the outset we weren’t sure if molecular signatures of gut contents would survive in the latrines over hundreds of years. Many of our successes in ancient bacterial retrieval thus far have come from calcified tissues like bones and dental calculus, which offer very different preservation conditions. Nevertheless,” says Bos, “I was really hoping the data here would change my perspective.”

The medieval latrine at Riga during excavation

The team analyzed sediment from medieval latrines in Jerusalem and Riga, Latvia dating from the 14th-15th century CE. The first challenge was distinguishing bacteria that once formed the ancient gut from those that were introduced by the environment, an unavoidable consequence of working with archaeological material.

The researchers identified a wide range of bacteria, archaea, protozoa, parasitic worms, fungi and other organisms, including many taxa known to inhabit the intestines of modern humans.

“It seems latrines are indeed valuable sources for both microscopic and molecular information,” concludes Bos.

No Modern Matches for Ancient Microbiomes

Susanna Sabin, a doctoral alumna of the MPI-SHH who co-led the study, compared the latrine DNA to those from other sources, including microbiomes from industrial and foraging populations, as well as waste water and soil.

“We found that the microbiome at Jerusalem and Riga had some common characteristics - they did show similarity to modern hunter gatherer microbiomes and modern industrial microbiomes, but were different enough that they formed their own unique group. We don’t know of a modern source that harbors the microbial content we see here.”

The use of latrines, where the faeces of many people are mixed together, allowed the researchers unprecedented insight into the microbiomes of entire communities.

“These latrines gave us much more representative information about the wider pre-industrial population of these regions than an individual faecal sample would have,” explains Mitchell. “Combining evidence from light microscopy and ancient DNA analysis allows us to identify the amazing variety of organisms present in the intestines of our ancestors who lived centuries ago.”

Despite the promise of this new approach for investigating the microbiome, challenges remain.

“We’ll need many more studies at other archaeological sites and time periods to fully understand how the microbiome changed in human groups over time,” says Bos. “However, we have taken a key step in showing that DNA recovery of ancient intestinal contents from past latrines can work.”